Skip to main content

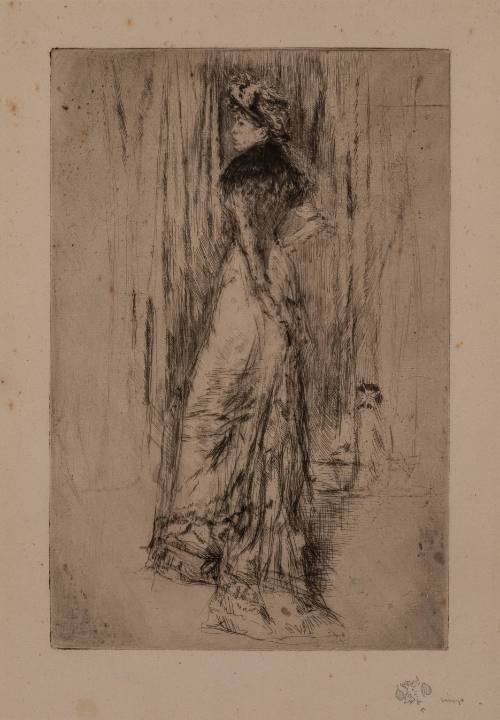

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

1834–1903

BirthplaceLowell, Massachusetts, United States of America

Death placeLondon, England

BiographyOne of the nineteenth century's most innovative, influential, and controversial artists, American expatriate James Abbott McNeill Whistler served as a bridge between European and American art worlds and laid the foundations for modernism in his iconoclastic art and writings. Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, but spent much of his childhood in St. Petersburg, Russia, where his father was a railroad engineer. Despite his considerable talent as a draftsman, Whistler was a failure both as a student at the United States military academy at West Point and as an employee of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. Determined to become an artist, he left for Europe in 1855, never to return to his native land, but he always considered himself an American artist.

Whistler spent his long career shuttling between the great art capitals of Paris and London. A boldly experimental artist in painting, printmaking, pastel drawing, and interior design, he became a link between several important artistic circles. In the 1860s these included the English painters known as the Pre-Raphaelites, who painted moralizing narrative works in obsessive detail, and the anti-academic French realist painters, led by Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), who looked to the inspiration of seventeenth-century Dutch and Spanish painting in their unsentimental treatments of contemporary social themes.

From the start, portraits, seascapes, and urban scenes were among Whistler's most important subjects. He broke ground not only in the modern nature of these themes but in his decorative treatments, which asserted pure surface values of composition, color, and texture as artistic ends. Inspired by the flat, reductive aesthetic of Japanese prints that began to flood Western markets in the 1860s, Whistler argued for an analogy between painting and music, a "pure" art independent of moral themes or even subject matter: he called his works "symphonies" and "nocturnes." His doctrine of "art for art's sake" laid the foundation for such diverse developments as the so-called aesthetic movement in art and design, which glorified pure pattern and color in richly decorated objects, and impressionism, the painted rendering of forms simply in terms of their reflection of colored light.

Charming, combative, and convinced of his own genius, Whistler was a flamboyant and even outrageous personality as provocative as his art. His relations with patrons, fellow artists, and critics were often contentious. In 1877, he sued John Ruskin (1819–1900) for libel after the conservative art critic condemned the painter for "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face"—a reference to the random splatterings of one of Whistler's "nocturnes." Whistler codified his controversial aesthetics in his famous "Ten O'Clock" lecture, delivered in 1885; it was soon translated into French and then published in London in 1890 in a collection of his writings entitled The Gentle Art of Making Enemies. By that date, Whistler's reputation was secured on both sides of the Atlantic, and he was much honored and admired by patrons and fellow artists alike.

Whistler spent his long career shuttling between the great art capitals of Paris and London. A boldly experimental artist in painting, printmaking, pastel drawing, and interior design, he became a link between several important artistic circles. In the 1860s these included the English painters known as the Pre-Raphaelites, who painted moralizing narrative works in obsessive detail, and the anti-academic French realist painters, led by Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), who looked to the inspiration of seventeenth-century Dutch and Spanish painting in their unsentimental treatments of contemporary social themes.

From the start, portraits, seascapes, and urban scenes were among Whistler's most important subjects. He broke ground not only in the modern nature of these themes but in his decorative treatments, which asserted pure surface values of composition, color, and texture as artistic ends. Inspired by the flat, reductive aesthetic of Japanese prints that began to flood Western markets in the 1860s, Whistler argued for an analogy between painting and music, a "pure" art independent of moral themes or even subject matter: he called his works "symphonies" and "nocturnes." His doctrine of "art for art's sake" laid the foundation for such diverse developments as the so-called aesthetic movement in art and design, which glorified pure pattern and color in richly decorated objects, and impressionism, the painted rendering of forms simply in terms of their reflection of colored light.

Charming, combative, and convinced of his own genius, Whistler was a flamboyant and even outrageous personality as provocative as his art. His relations with patrons, fellow artists, and critics were often contentious. In 1877, he sued John Ruskin (1819–1900) for libel after the conservative art critic condemned the painter for "flinging a pot of paint in the public's face"—a reference to the random splatterings of one of Whistler's "nocturnes." Whistler codified his controversial aesthetics in his famous "Ten O'Clock" lecture, delivered in 1885; it was soon translated into French and then published in London in 1890 in a collection of his writings entitled The Gentle Art of Making Enemies. By that date, Whistler's reputation was secured on both sides of the Atlantic, and he was much honored and admired by patrons and fellow artists alike.