Skip to main content

Thomas Eakins

1844–1916

BirthplacePhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Death placePhiladelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America

BiographyLong considered an American master of realism, Thomas Eakins devoted his portraits and scenes of everyday life to a penetrating exploration of the life and people around him in late-nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Eakins’s father, a writing master, encouraged his son’s artistic interests and ultimately gave him a modest financial independence, facilitating his artistic freedom. After receiving a solid grounding in technical drawing and science at Philadelphia’s Central High School, Eakins enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1866, he left Philadelphia for four years of study in Europe. In Paris he worked under the French painter Jean-Léon Gerôme (1824–1904), known for his precisely rendered exotic and historical scenes. He also studied under portrait painter Léon Bonnat (1833–1922). On Bonnat’s advice, Eakins visited Spain, where he was particularly impressed by the work of the great painters of the Baroque era.

Eakins returned permanently to Philadelphia, hoping to establish himself as a portraitist. His earliest paintings were carefully observed scenes of family life that anticipate both his images of sport and the psychological emphasis of his mature work. Convinced of the importance of scientific understanding of the body to his artistic work, he took up the study of anatomy at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. His groundbreaking portrait, The Gross Clinic (1875, jointly owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), which shows Dr. Samuel D. Gross performing a surgical operation in a crowded amphitheater, was considered too shocking to be exhibited among the artworks at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and was relegated to the fair’s medical display. This was the first of a series of confrontations between the uncompromising artist and institutional authorities, patrons, and even fellow artists.

Dedicating his art to discovering the heroism of modern life, Eakins was especially drawn to subjects that honored well-honed skill, whether in intellectual pursuits or in sport. In addition, in the year of the centennial, Eakins began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy, where he stressed the rigorous pedagogy—grounded in careful drawing and in scientific study of the human form—that he had learned in France. Eakins was a popular and influential teacher, but his insistence that both his male and female students draw from unclothed models of both sexes brought him into conflict with the institution that finally dismissed him a decade later. By that date, he had married Susan Macdowell, a talented painter and former student, who became his lifelong champion. In the 1880s, Eakins became an avid, innovative photographer, using photography as he had earlier used drawing: as the foundation of rigorously truthful expression in his paintings.

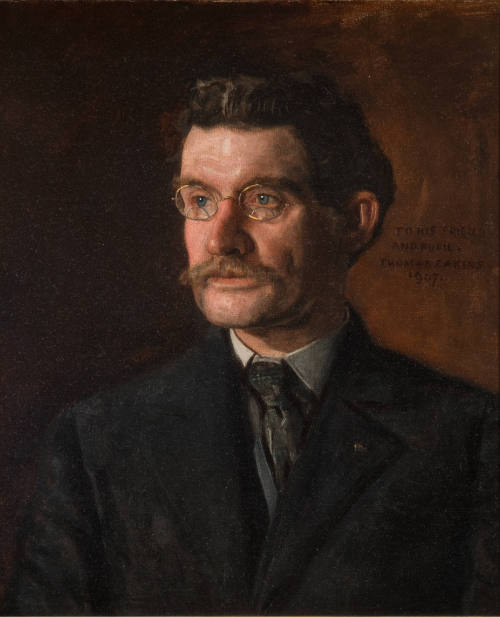

From around 1890 to the end of his life, Eakins devoted himself obsessively to portraits. Unable to attract commissions because of his refusal to flatter in his likenesses, he portrayed friends, family members, and acquaintances in focused images that combine a detached realism and conventional formats with almost painful psychological intensity. These late works are the culminating expression of the artist’s career-long endeavor to capture the inner reality of modern existence, an achievement that has earned Eakins a place as one of America’s most important artists.

Eakins returned permanently to Philadelphia, hoping to establish himself as a portraitist. His earliest paintings were carefully observed scenes of family life that anticipate both his images of sport and the psychological emphasis of his mature work. Convinced of the importance of scientific understanding of the body to his artistic work, he took up the study of anatomy at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. His groundbreaking portrait, The Gross Clinic (1875, jointly owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts), which shows Dr. Samuel D. Gross performing a surgical operation in a crowded amphitheater, was considered too shocking to be exhibited among the artworks at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and was relegated to the fair’s medical display. This was the first of a series of confrontations between the uncompromising artist and institutional authorities, patrons, and even fellow artists.

Dedicating his art to discovering the heroism of modern life, Eakins was especially drawn to subjects that honored well-honed skill, whether in intellectual pursuits or in sport. In addition, in the year of the centennial, Eakins began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy, where he stressed the rigorous pedagogy—grounded in careful drawing and in scientific study of the human form—that he had learned in France. Eakins was a popular and influential teacher, but his insistence that both his male and female students draw from unclothed models of both sexes brought him into conflict with the institution that finally dismissed him a decade later. By that date, he had married Susan Macdowell, a talented painter and former student, who became his lifelong champion. In the 1880s, Eakins became an avid, innovative photographer, using photography as he had earlier used drawing: as the foundation of rigorously truthful expression in his paintings.

From around 1890 to the end of his life, Eakins devoted himself obsessively to portraits. Unable to attract commissions because of his refusal to flatter in his likenesses, he portrayed friends, family members, and acquaintances in focused images that combine a detached realism and conventional formats with almost painful psychological intensity. These late works are the culminating expression of the artist’s career-long endeavor to capture the inner reality of modern existence, an achievement that has earned Eakins a place as one of America’s most important artists.