Skip to main content

Charles Burchfield

1893–1967

BirthplaceAshtabula Harbor, Ohio, United States of America

Death placeWest Seneca, New York, United States of America

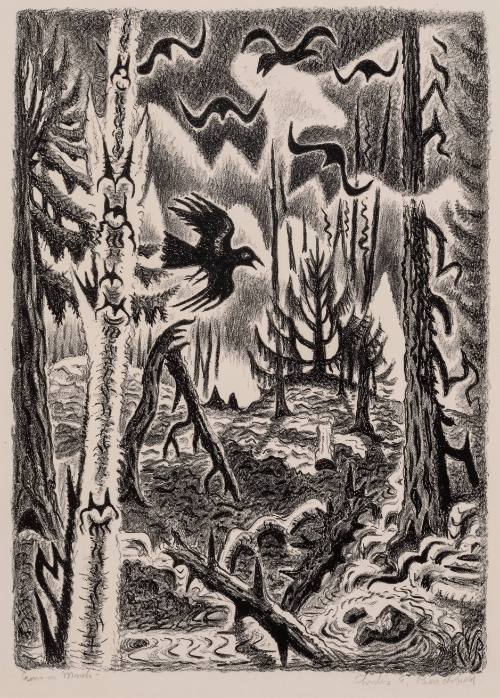

BiographyRanging from the straightforwardly realistic to the fantastic, master watercolor painter Charles Burchfield's images of nature and streetscapes of small-town America are imbued with the mystical energy of his idiosyncratic vision. The son of a tailor who died when he was six, Burchfield was raised in Salem, Ohio by his mother, a former schoolteacher. A shy child, he was drawn to the surrounding countryside, which he passionately drew as he explored it. Graduating from high school in 1911 at the top of his class, he enrolled at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art). An aborted sojourn in New York City, where he had been accepted into the prestigious National Academy of Design, convinced Burchfield that he belonged in the hinterland of his youth, with nature close at hand. In 1916 and 1917, while working as a cost accountant for a metal fabricator in Salem, Burchfield experienced a creative surge yielding some two hundred paintings of emotion-laden nature imagery that drew on a rich vocabulary of fantasy nurtured since childhood. From the beginning of his artistic career he worked almost exclusively in the fluid medium of watercolor, with the addition of gouache (an opaque water-based paint) and various drawing media.

Beginning in 1919, Burchfield's encounter with the novels of Midwestern contemporary writer Sherwood Anderson turned his attention to the expressive potential of the often decayed old houses and factories typical of Midwestern towns he sketched along the Ohio River Valley. With his marriage in 1922, Burchfield moved to Buffalo, New York, to work as a wallpaper designer, painting in his spare time the city's somber industrial landscape in a relatively restrained style. Seven years later, the artist established a relationship with New York City art dealer Frank Rehn that allowed him finally to devote himself full time to his art. As Burchfield's fame spread, he was troubled to be associated with the so-called regionalist school led by such figures as Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood, preferring to be seen simply as an American artist, albeit one outside the mainstream. However, his work shares the regionalists' dedication to the American heartland as a well-spring of subjects and inspiration, a world in which mythic drama and mystery are apparent in the prosaic and everyday.

In the early 1940s, partly prompted by his conversion to Lutheranism, his wife's faith, Burchfield returned to the natural landscape with renewed conviction. He reworked his early watercolors, often incorporating them into larger compositions by painting on strips of paper added to the edges. These monumental, visionary paintings evince a quasi-religious embrace of nature. They met with only mixed financial success, and Burchfield turned intermittently to alternate sources of income, such as teaching and printmaking. However, by 1956, when he was the subject of a comprehensive exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art, the artist had long been recognized and honored with invitations to serve on exhibition juries, gold medals, and election to the National Academy of Arts and Letters. Burchfield's art was realizing a new intensity of expressive vision when he died of a heart attack at the age of seventy-three.

Beginning in 1919, Burchfield's encounter with the novels of Midwestern contemporary writer Sherwood Anderson turned his attention to the expressive potential of the often decayed old houses and factories typical of Midwestern towns he sketched along the Ohio River Valley. With his marriage in 1922, Burchfield moved to Buffalo, New York, to work as a wallpaper designer, painting in his spare time the city's somber industrial landscape in a relatively restrained style. Seven years later, the artist established a relationship with New York City art dealer Frank Rehn that allowed him finally to devote himself full time to his art. As Burchfield's fame spread, he was troubled to be associated with the so-called regionalist school led by such figures as Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood, preferring to be seen simply as an American artist, albeit one outside the mainstream. However, his work shares the regionalists' dedication to the American heartland as a well-spring of subjects and inspiration, a world in which mythic drama and mystery are apparent in the prosaic and everyday.

In the early 1940s, partly prompted by his conversion to Lutheranism, his wife's faith, Burchfield returned to the natural landscape with renewed conviction. He reworked his early watercolors, often incorporating them into larger compositions by painting on strips of paper added to the edges. These monumental, visionary paintings evince a quasi-religious embrace of nature. They met with only mixed financial success, and Burchfield turned intermittently to alternate sources of income, such as teaching and printmaking. However, by 1956, when he was the subject of a comprehensive exhibition at New York's Whitney Museum of American Art, the artist had long been recognized and honored with invitations to serve on exhibition juries, gold medals, and election to the National Academy of Arts and Letters. Burchfield's art was realizing a new intensity of expressive vision when he died of a heart attack at the age of seventy-three.