Skip to main content

Edmund C. Tarbell

1862–1938

BirthplaceWest Groton, Massachusetts, United States of America

Death placeNew Castle, New Hampshire, United States of America

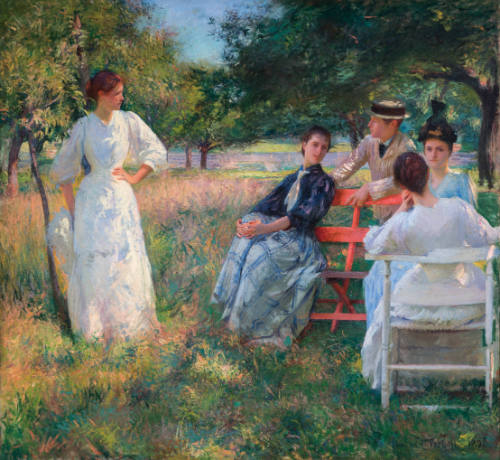

BiographyIn his outdoor and interior scenes of family members at leisure, Edmund C. Tarbell helped develop an American idiom of impressionism, the painting of everyday modern life with particular attention to light effects. Of an old New England family, Tarbell was raised in West Groton, Massachusetts, and Boston. He studied art briefly at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and worked for a lithographic publisher before enrolling at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. There, he met Frank W. Benson, who became a close colleague. Tarbell went to Paris in 1884 to study at the Académie Julian, where the academic course of study emphasized the human figure; he also traveled in Germany and visited Venice and London.

Following his return to Boston in 1886, Tarbell married Emeline Arnold Souther, a former fellow art student, and with Benson began teaching at and then co-directing the Boston Museum School, where he remained until 1912. He frequently exhibited his paintings of single female figures—family members—in dimly lit interiors. In 1890 he began posing his subjects outdoors in the dappled light of a fair summer day. When toward the end of the decade Tarbell returned to interior settings it was to create adventurous compositions that evince the influence both of French impressionist painting and of Japanese woodblock prints in their asymmetry and tipped-up perspective. These paintings won considerable notice and were emulated by some of Tarbell’s students and contemporaries, who were dubbed the Tarbellites by a sympathetic critic. Along with Benson, Tarbell represented this “Boston School” of impressionism as a founding member of Ten American Painters, or The Ten. Between 1898 and 1918, this organization of American impressionist painters held exhibitions independent of those sponsored by the powerful National Academy of Design.

In addition to portraits, complex scenes of figures in interiors remained the mainstay of Tarbell’s career. His wife and four children served repeatedly as his models. Posed as if casually and unselfconsciously engaged in such everyday activities as reading, needlework, and letter-writing, these figures represent a life of genteel domesticity apparently untainted by the grimmer realities of contemporary American urbanization, labor conflict, and social strife. Tarbell gave equal weight to the dusky rooms they comfortably occupy: interiors of summer residences, notably the old house in New Castle, on the New Hampshire coast, that the artist purchased in 1905 and lovingly expanded. The house served not just as the setting for the idealized harmonious life he pictured but as his personal link to his New England heritage, one that connected him with his elite patrons. A similar aristocratic spirit infuses Tarbell’s many paintings of his children and later grandchildren with their horses.

After serving for several years as head of the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., the artist retired in 1918 to his New Castle home. He continued painting there until his death at age seventy-six, just before the opening of a joint exhibition with Benson at the Boston Museum.

Following his return to Boston in 1886, Tarbell married Emeline Arnold Souther, a former fellow art student, and with Benson began teaching at and then co-directing the Boston Museum School, where he remained until 1912. He frequently exhibited his paintings of single female figures—family members—in dimly lit interiors. In 1890 he began posing his subjects outdoors in the dappled light of a fair summer day. When toward the end of the decade Tarbell returned to interior settings it was to create adventurous compositions that evince the influence both of French impressionist painting and of Japanese woodblock prints in their asymmetry and tipped-up perspective. These paintings won considerable notice and were emulated by some of Tarbell’s students and contemporaries, who were dubbed the Tarbellites by a sympathetic critic. Along with Benson, Tarbell represented this “Boston School” of impressionism as a founding member of Ten American Painters, or The Ten. Between 1898 and 1918, this organization of American impressionist painters held exhibitions independent of those sponsored by the powerful National Academy of Design.

In addition to portraits, complex scenes of figures in interiors remained the mainstay of Tarbell’s career. His wife and four children served repeatedly as his models. Posed as if casually and unselfconsciously engaged in such everyday activities as reading, needlework, and letter-writing, these figures represent a life of genteel domesticity apparently untainted by the grimmer realities of contemporary American urbanization, labor conflict, and social strife. Tarbell gave equal weight to the dusky rooms they comfortably occupy: interiors of summer residences, notably the old house in New Castle, on the New Hampshire coast, that the artist purchased in 1905 and lovingly expanded. The house served not just as the setting for the idealized harmonious life he pictured but as his personal link to his New England heritage, one that connected him with his elite patrons. A similar aristocratic spirit infuses Tarbell’s many paintings of his children and later grandchildren with their horses.

After serving for several years as head of the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., the artist retired in 1918 to his New Castle home. He continued painting there until his death at age seventy-six, just before the opening of a joint exhibition with Benson at the Boston Museum.