Skip to main content

Thomas Hart Benton

1889–1975

BirthplaceNeosho, Missouri, United States of America

Death placeKansas City, Missouri, United States of America

BiographyBorn into a family of politics and privilege in southwestern Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton was named after his great-uncle, the state’s esteemed six-term senator. Benton first studied art as a child at the School of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., then pursued formal artistic training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, beginning in 1906. Two years later, he traveled to Paris where he briefly studied at the Académie Julien and enjoyed the bohemian lifestyle of a young art student. More importantly, however, he embraced the French capital’s art scene, experimenting with abstraction and non-representational imagery.

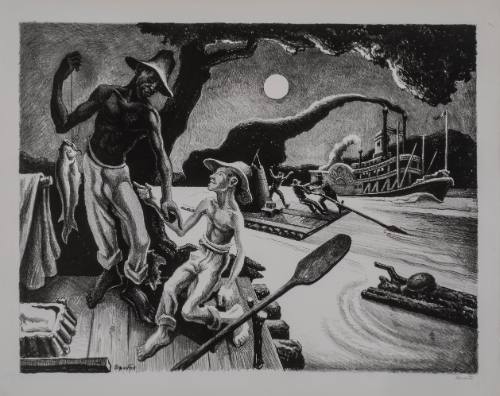

By 1912, Benton had settled in New York City, which became the center of his professional life for the next two decades. Notable for his early embrace of modernist art theory, Benton melded his formalist concerns regarding figuration and realism with the practice of avant-garde painting in order to establish a uniquely American idiom. His depictions of everyday life and frequent portrayal of violence were anything but reverential of America’s cultural past, however, and his murals, such as the American Historical Epic series (1919–1928), often provoked public debate. Nevertheless, Benton’s reputation as America’s leading muralist was established when he completed America Today in 1931 for the New School of Social Research in New York. Following the cycle’s critical acclaim, Benton returned to the Midwest to execute a mural commission for the Indiana State Pavilion at Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair. He later relocated to Kansas City, Missouri, where he lived and worked until his death in 1975.

Benton’s impact extended far beyond his own practice of painting, drawing, and printmaking. His authoritative voice as a teacher manifested in his most famous student, Jackson Pollock, who not only learned from Benton his comprehensive method of composition but also how to create a sense of visual rhythm on a static canvas. Until recently Benton and other regionalist painters were disparaged by formalist critics as the antitheses of the modern artist. However, scholars now recognize the plurality of modernisms in the 1920s and 30s, acknowledging that artists, critics, and patrons of the era prized individualism as the ultimate expression of a modern outlook. Benton, within this new historiographic context, has emerged as a determined modernist and pioneering American Scene painter whose work, along with that of his like-minded contemporaries Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, was informed by varied and complex theoretical attitudes that he articulated in a distinctively dynamic and innovative style.

By 1912, Benton had settled in New York City, which became the center of his professional life for the next two decades. Notable for his early embrace of modernist art theory, Benton melded his formalist concerns regarding figuration and realism with the practice of avant-garde painting in order to establish a uniquely American idiom. His depictions of everyday life and frequent portrayal of violence were anything but reverential of America’s cultural past, however, and his murals, such as the American Historical Epic series (1919–1928), often provoked public debate. Nevertheless, Benton’s reputation as America’s leading muralist was established when he completed America Today in 1931 for the New School of Social Research in New York. Following the cycle’s critical acclaim, Benton returned to the Midwest to execute a mural commission for the Indiana State Pavilion at Chicago’s 1933 World’s Fair. He later relocated to Kansas City, Missouri, where he lived and worked until his death in 1975.

Benton’s impact extended far beyond his own practice of painting, drawing, and printmaking. His authoritative voice as a teacher manifested in his most famous student, Jackson Pollock, who not only learned from Benton his comprehensive method of composition but also how to create a sense of visual rhythm on a static canvas. Until recently Benton and other regionalist painters were disparaged by formalist critics as the antitheses of the modern artist. However, scholars now recognize the plurality of modernisms in the 1920s and 30s, acknowledging that artists, critics, and patrons of the era prized individualism as the ultimate expression of a modern outlook. Benton, within this new historiographic context, has emerged as a determined modernist and pioneering American Scene painter whose work, along with that of his like-minded contemporaries Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, was informed by varied and complex theoretical attitudes that he articulated in a distinctively dynamic and innovative style.