Skip to main content

Dated Web objects before 1800 through 1839

24 results

Thomas Cole

Date: 1826

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1993.2

Text Entries: (modified anniversary publication entry) The English-born painter Thomas Cole, a key figure of the Hudson River School, recognized the epic potential of the American landscape. On his arrival in Philadelphia at the age of seventeen, he had already been apprenticed to an engraver and soon turned his interest to painting. He later moved to New York City and, inspired by the magnificent vistas along the Hudson River, began to define landscape as a spiritual subject that could transcend its function as a mere topographical record. In this way, Cole contributed to the romantic transformation of landscape painting from documentary and picturesque views into a discourse on the human experience set against the enduring forces of nature, elevating the once modest genre of landscape painting to an expression of the heroic sublime.

In Landscape with Figures: A Scene from "The Last of the Mohicans" the human figures are dwarfed by an awe-inspiring vista of towering mountains and an expansive sky. Cole portrays the denouement of James Fenimore Cooper's newly published, popular novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826). The painting visualizes the novel's climactic scene in which the hero frontiersman Hawkeye aims his shotgun at Magua, the native villain, who tries to flee down a cliff. Cora Munro, the heroine of the novel, after being kidnapped and brutalized by Magua, lies dying at Hawkeye's feet. The grandeur of Cole's autumnal wilderness of scarlet leaves and wild rushing mountain streams overwhelms the narrative, however, reminding the viewer that there are greater forces in the universe than human conflict and desire.

Ammi Phillips

Date: 1827

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1992.56

Text Entries: Ammi Phillips, from Colebrook, Connecticut, advertised as an itinerant painter in New England newspapers, describing his ability to capture: "a correct style, perfect shadows, and elegant dresses." To promote a pleasing likeness, Phillips offered to supply costumes for his subjects-also a practice of painter Erastus Salisbury Field. Phillips developed a strong clientele base by integrating himself into various communities long enough to be considered the logical choice for portrait commissions.

Phillips painted the fair-skinned, six-month old Mary Elizabeth Smith (later Mrs. S. Canfield) an only child from Orange County, New York, against the reddish-black "mulberry" colored background typical of his 1820s works. This painting, representative of the history of many folk portraits, remained in the family before entering the Terra Foundation for the Arts collection. The baby, wearing a delicately rendered white eyelet dress and bonnet, clasps a sprig of ripening strawberries, symbolizing her gender and youth. Children and adults of the nineteenth century often wore coral necklaces for adornment although they previously signified protection against illness and misfortune.

Edward Hicks

Date: c. 1829-1830

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1993.7

Text Entries: (modified anniversary publication entry) Edward Hicks gained a reputation in his community for his work as an ornamental painter and his outspoken participation in the Society of Friends, popularly known as the Quakers. A lifelong resident of rural Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Hicks had a limited formal education. At the age of thirteen, he apprenticed to a coach painter. Later he married and set up shop painting signs, coaches, and other utilitarian objects. This profession was in conflict with the spare life advocated by his faith, and his increasing activity as a traveling minister kept him away from his business. Why or when Hicks turned to easel painting is unknown, but about 1820 he began to explore an allegorical subject that he found infinitely variable and satisfying. A Peaceable Kingdom with Quakers Bearing Banners portrays the tolerant coexistence among all the animals and humanity described in Isaiah 11: 6-9. Depicting wildness calmed by gentleness and worldliness tempered by innocence, the message of the Peaceable Kingdom became for Hicks a form of testament, a painted articulation of his deepest beliefs.

A Peaceable Kingdom with Quakers Bearing Banners places Hicks at the center of a religious controversy that split the Quakers into factions. Hicks' elderly cousin Elias promoted an extreme form of Quaker quietism, in which the faithful were urged to discard all but the most basic elements of daily life to open themselves to divine grace and be guided by the Inward Light of Christ. Elias and his followers, known as Hicksites, withdrew from the Quaker Orthodoxy, prompting accusations of heresy. A series of one hundred Banner paintings by Hicks announce his solidarity with his cousin's beliefs, while calling for peaceful coexistence among the factions.

Standing in the front row of the figures at the left and holding a handkerchief he used to mop his brow when preaching, Elias Hicks is accompanied by George Washington and William Penn. The Apostles stand behind them. The banners read "mind the LIGHT within IT IS GLAD TIDEING of Grate Joy PEACE ON EARTH GOOD WILL to ALL MEN everywhere," the words of the Apostle Luke and a basic tenet of the Quaker faith.

Samuel F. B. Morse

Date: 1831–33

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1992.51

Text Entries: Samuel F. B. Morse championed the fine arts in the United States but believed there were benefits from studying the best examples of Old World culture. He conceived Gallery of the Louvre as an instructive lesson on European painting that would tour the United States. During its brief exhibition in New York City, however, the painting failed to attract an audience. Its mostly Protestant viewers, schooled in democratic principles, had misgivings when confronted with art that endorsed monarchy, an aristocratic elite and Catholicism.

American art lovers, though, were already familiar with European art that had been transformed by American artists to suit the needs of a newly founded Republic-landscapes, portraits and, surprisingly, religious motifs. These European prototypes are found in the miniaturized paintings incorporated in Gallery of the Louvre and can be compared to their American adaptations. Although he employed the compositional techniques of Nicolas Poussin's (1594-1665) "classical landscape" painting, William Groombridge's View of a Manor House-which depicts the site of George Washington's headquarters for the first victory in the Revolutionary War-reinterprets an ideal landscape as democratic.

Portraiture was easily adjusted to serve a democracy, whose free market system celebrated the individual. The enigmatic smile of Thomas Sully's beautiful daughter Blanch suggests a comparison with Leonardo da Vinci's (1452-1519) portrait of Mona Lisa. Erastus Field's naïve-style portrait of Clarissa Cook, commissioned by her well-to-do family, provides clues to her family's material success in the same manner as Peter Paul Rubens's (1577-1640) elegant portrayal of a wealthy businessman's wife.

Portraits of children celebrate both the individual while also serving as a symbol for the young country, as seen in itinerant painter Ammi Phillips's portrait of Mary Elizabeth Smith. In a similar fashion, Bartolomé Murillo's (1617-1682) naturalistic portrayal in A Beggar Boy represents an idealized childhood that serves as a Spanish national emblem. Genre subjects were introduced into American art through engravings of seventeenth and eighteenth century Dutch and British scenes of daily life. Using familiar figures and their gestures found in European art, John Lewis Krimmel in Blind Man's Buff created a new art form that suited the needs of a new democratic state.

Revisiting a theme associated with Catholic art, many examples of which are found in Morse's picture, John James Barralet's Apotheosis of Washington demonstrates the difficulty in transforming a biblical image to honor a cultural hero. Likewise, while Morse's grand experiment to teach art history through Gallery of the Louvre met resistance, he succeeded in creating an icon of transatlantic cultural exchange.

Samuel F. B. Morse

Date: between 1831 and 1832

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Gift of Berry-Hill Galleries in honor of Daniel J. Terra

Object number: C1984.5

Text Entries: Kloss, William. <i>Samuel F.B. Morse</i>. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., Publishers in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1988. Text p. 130, ill. p. 131 (color).<br><br>

Reymond, Nathalie. <i>Un regard américain sur Paris</i> (<i>An American Glance at Paris</i>). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 1997. Text p. 70; ill. p. 67 (color).<br><br>

Cartwright, Derrick R. <i>The Extraordinary and the Everyday: American Perspectives, 1820–1920</i>. (exh. cat., Musée d'Art Américain Giverny). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2001. Text p. 24 (checklist).<br><br>

Cartwright, Derrick R. <i>L'Héroïque et le quotidian: les artistes américains, 1820–1920</i>. (exh. cat., Musée d'Art Américain Giverny). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2001. Text p. 24 (checklist).<br><br>

Bourguignon, Katherine M. and Elizabeth Kennedy. <i>An American Point of View: The Daniel J. Terra Collection</i>. Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2002. Text p. 50.<br><br>

Bourguignon, Katherine M. and Elizabeth Kennedy. <i>Un regard transatlantique. La collection d'art américain de Daniel J. Terra</i>. Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2002. Text p. 50.<br><br>

Brownlee, Peter John. <i>A New Look: Samuel F. B. Morse's "Gallery of the Louvre."</i> (exh. brochure, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2011. Text, p. 3; ill. fig. 4 (color).<br><br>

Brownlee, Peter John. <i>Samuel F. B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention</i>. (exh. cat., The Huntington Library, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Seattle Art Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Peabody Essex Museum, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, New Britain Museum of American Art). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2014. Text p. 24, 103; ill. p. 24 (color).<br><br>

Joseph H. Davis

Date: c. 1832–38

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1992.30

Text Entries: <i>Two Centuries of American Folk Painting, </i>Terra Museum of American Art, Evanston, Illinois (organizer). Venue: Terra Museum of American Art, Evanston, Illinois, February 10–April 21, 1985.<br><br>

Collection Cameo companion piece, Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois, January 2000.<br><br>

<i>Figures and Forms: Selections from the Terra Foundation for the Arts, </i>Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois (organizer). Venue: Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois, May 9–July 9, 2000.<br><br>

<i>A Rich Simplicity: Folk Art from the Terra Foundation for the Arts Collection, </i>Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois (organizer). Venue: Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois, June 7–September 21, 2003.<br><br>

<i>Visages de l'Amérique: de George Washington à Marilyn Monroe</i> (<i>Faces of America: From George Washington to Marilyn Monroe</i>), Musée d'Art Américain Giverny, France (organizer). Venue: Musée d'Art Américain Giverny, France, April 1–October 31, 2004 (on exhibition partial run: April 1–July 5, 2004). [exh. cat.]

Washington Allston

Date: 1832

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition Endowment Fund

Object number: 2000.3

Text Entries: <i>An Exhibition of Pictures Painted by Washington Allston</i>. (exh. cat., Harding's Gallery). Boston, Massachusetts: Harding's Gallery, 1839. No. 38, p. 7.<br><br>

Ticknor, William D. <i>Remarks on Allston's Paintings</i>. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 1839. Text pp. 9–11.<br><br>

Ware, William. <i>Lectures on the Works and Genius of Washington Allston</i>. Boston, Massachusetts: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1852. Text pp. 75–77.<br><br>

Flagg, Jared B. <i>The Life and Letters of Washington Allston</i>. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1892. Text p. 392.<br><br>

<i>Brooklyn Museum Quarterly</i> 2 (April–October 1915): 283.<br><br>

Richardson, Edgar Preston. <i>Washington Allston: A Study of the Romantic Artist in America</i>. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1948. Text pp. 149, 181; pl. LIII, no. 138, p. 21.<br><br>

Gerdts, William H. and Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. <i>A Man of Genius: The Art of Washington Allston</i>. (exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Boston, Massachusetts: Museum of Fine Arts, 1979. Text pp. 141, 143, 147, 169; ill. p. 198, no. 64 (black & white).<br><br>

Mandeles, C. "Allston's <i>The Evening Hymn." Arts</i> 54 (January 1980): 142–45. Ill. (black & white).<br><br>

Feld, Stuart P. <i>Boston in the Age of Neo-Classicism, 1810-1840</i>. (exh. cat., Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc.). New York: Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc., 1999. Text p. 122; ill. p. 123, no. 75 (color).<br><br>

Bourguignon, Katherine M. and Elizabeth Kennedy. <i>An American Point of View: The Daniel J. Terra Collection</i>. Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2002. Text p. 52, 191; ill. pp. 5 (color), 53 (color), 191 (black & white).<br><br>

Bourguignon, Katherine M. and Elizabeth Kennedy. <i>Un regard transatlantique. La collection d'art américain de Daniel J. Terra</i>. Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2002. Text p. 52, 191; ill. pp. 5 (color), 53 (color), 191 (black & white).<br><br>

<i>Side by Side: Works from the Terra Foundation for the Arts and the Detroit Institute of Arts</i>. (exh. cat., Musée d'Art Américain Giverny). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2003. Text p. 5; ill. p. 4 (color).<br><br>

<i>Deux collections en regard: oeuvres de la Terra Foundation for the Arts et du Detroit Institute of Arts</i>. (exh. cat., Musée d'Art Américain Giverny). Chicago, Illinois: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2003. Text p. 5; ill. p. 4 (color).

Bourguignon, Katherine M., and Peter John Brownlee, eds. <i>Conversations with the Collection: A Terra Foundation Collection Handbook.</i> Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2018. Text pp. 24–26, 37; fig. 4, p. 25; ill. p. 37 (color).<br><br>

Joseph H. Davis

Date: 1833

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1992.31

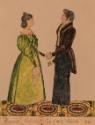

Text Entries: Many early-nineteenth-century paintings of young adults depict courtship or engagement, as might this one. Although books commonly symbolized refinement and frequently appear in Davis's portraits, this book joins the couple, perhaps emphasizing their pending union. The unpainted background accentuates the fashionable couple's costume and coiffure which are rendered with crisp precision. The colorful decorative carpet or stenciled floor provides visual weight that helps to anchor the figures in space.

Joseph H. Davis

Date: 1834

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1999.36

Text Entries: Joseph H. Davis, of New Hampshire and Maine, primarily painted profile likenesses of New England residents in watercolor on paper, a less expensive and more convenient medium to travel with than oil paint and canvas. In his distinct style, Davis rendered facial features with linear precision and objects signifying refined middle-class taste with meticulous description.

Several Davis trademarks appear in this watercolor: the sitters' names and ages and the date appear in skillful calligraphic lettering along the base of the painting and a framed picture above a table-in this case, a farm-typically a reference to the sitter's home or business.

Samuel wears a plain suit, which communicated respectability and personal achievement during this time of emerging American capitalism. His colorfully decorated soft cap, an accessory worn at home or in casual situations, stands in contrast to his somber costume. Mary Vickery's dress expresses prosperity through the fine delicate quality of her lace apron, her fringed red kerchief, and the rich blue gown with large puffed sleeves that were in vogue from 1825 to 1840.

Ammi Phillips

Date: c. 1835

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection

Object number: 1992.57

Text Entries: (modified anniversary publication entry) In 1809 Ammi Philips began advertising his services as a portraitist and his prolific success as a portrait painter spanned more than fifty years. Demand for portraits steadily increased with the rise of the nation's merchant and middle classes, and self-trained artists like Phillips made a living traveling from town to town painting on commission. Unlike many itinerant artists, however, Phillips often settled, with his family, in a town or village for several years at a time, only moving on when he had exhausted the possibilities for employment in that community.

Although many of his works are neither signed nor dated, ongoing scholarship has carefully reconstructed Phillips' oeuvre by tracing his career through county and town records, land deeds, and a collection of official documentation that places the artist in specific regions during certain years. Stylistically linked to a period between 1830 and 1835, Girl in a Red Dress exemplifies the artist's method of using an interchangeable stock of garments and props for his portraits. The painting is one of several similar likenesses in which a young sitter wears a wide-necked red dress, coral necklace, and pulled-back hair surrounded by a dog, carpet, and berries (following the eighteenth-century portrait tradition of using emblematic attributes, Phillips' incorporation of the puppy and berries represents, respectively, the sitter's fidelity and youthful vitality). This stylistic streamlining would not only save time and money for the artist, but would also ensure that each new client would have a reasonable idea of what to expect from the finished product.

Erastus Salisbury Field

Date: c. 1838

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition Endowment Fund

Object number: 2000.4

Text Entries: Painter Erastus Salisbury Field of Leverett, Massachusetts, enjoyed a prolific and prosperous career of sixty-five years. After brief instruction in 1824 from Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872), Field crossed New England to paint portraits of rural society figures. The 1830s were productive for Field: he refined his artistic skills, developed an increasingly personal style and obtained commissions through a network of family associations.

Field painted several portraits of residents from Petersham, Massachusetts, among them the Cook and Gallond families. In this portrait said to be Clarissa Gallond Cook, Field skillfully portrayed the sitter's prominent brow and long nose as well as her modishly styled hair of the mid-1830s.

The unusual background shows an unidentifiable port city, perhaps along the Hudson River where the Cook family sailed their merchant schooner, the "Sarah Taintor." Instead of a traditional feminine landscape setting, the female sitter is posed before a background suggestive of trade and industry more typically found in male portraits. A similarly provocative background appears in a Field portrait from the Shelburne Museum in Vermont. The identification of the sitter remains in question. She may be one of Clarissa's sisters, Almira Gallond Moore or Louisa Gallond Cook, who also married into the Cook family.

Thomas Sully

Date: 1839

Credit Line: Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Art Acquisition Endowment Fund

Object number: 2000.2

Text Entries: Roughly contemporary, these two portraits each depict a member of the artist's family. Jonathan Adams Bartlett's "likeness" of his sister, Harriet, is exceptional in its inclusion of books-both in her hand and stacked on the table-a nod to the intellectual realm most associated with men. Though fashionably rouged and coifed, Harriet is nevertheless portrayed as actively seeking knowledge: her over-the-shoulder look at the viewer seems to indicate an interruption of activity-a moment captured-additionally emphasized by the tassel caught in mid-swing behind her.

Likewise, Thomas Sully portrays his daughter Blanch with a fashionable hairstyle and headdress, which serve in effect to "crown" her head. Sully executed this canvas soon after returning home from painting the commissioned portrait of the young Queen Victoria. Interestingly, the twenty-one year old Blanch accompanied her father to London and often modeled in the queen's stead between sessions. The painting of Blanch serves as a visual poem to her intelligence, beauty and charm. Like Bartlett, Sully relied on visual symbols to convey an inner truth of individual character.