Skip to main content

George Bellows

1882–1925

BirthplaceColumbus, Ohio, United States of America

Death placeNew York, New York, United States of America

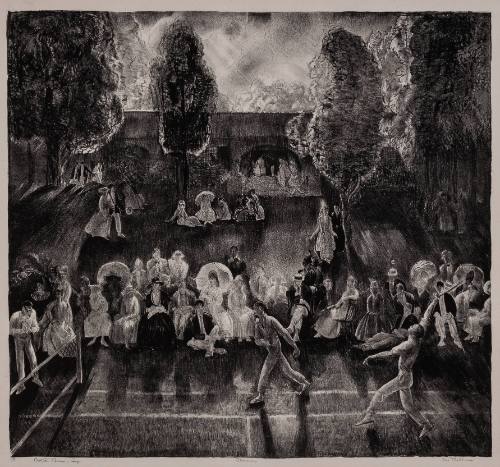

BiographyAn artist who embraced a realist, reportorial approach as well as contemporary art theory, George Bellows recorded the world around him in powerful landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and scenes of everyday life and historical events. Bellows was born into a conservative, middle-class family in Columbus, Ohio. As a youth he showed an interest in drawing and a talent for athletics. He abandoned his studies at Ohio State University to play semi-professional baseball; this employment, along with the sale of his drawings, helped support his art training under famed teacher and realist painter Robert Henri at the New York School of Art beginning in 1904. Unlike many artists of his generation, Bellows never traveled abroad.

Henri inspired Bellows to turn his attention to the portrayal of city life around him. Throughout his career, New York City and its inhabitants were an important fund of subjects. Bellows explored the variety of the city, from middle-class matrons in Central Park to poor urban youth at play and prizefighters locked in combat, and from the busy Hudson River to construction sites. In addition to such gritty urban themes, Bellows painted the sea and seafaring folk on the coast of Maine and idyllic rural life in Middletown, Rhode Island, and Woodstock, New York. He was also a prolific painter of portraits, both of sitters for commissioned likenesses and of family members. During World War One he began to produce dramatic images of the conflict and its heroes and victims. Bellows treated these themes not only in vigorously painted, strongly colored oils but in lithographic prints, which he began to produce in 1916. Since early in his career he had drawn illustrations for magazines ranging from conservative journals to The Masses, an organ of progressive politics.

Although never officially a member, Bellows exhibited with the group of radical realist artists known as The Eight; a critic derisively called them “the Ashcan school” because their paintings focused on the seamier side of urban life using a vigorous, anti-academic style. Bellows’s work shared these features, but it was also well-received by critics and fellow artists, even conservatives: for example, in 1909, he was the youngest associate member ever elected to New York’s prestigious National Academy of Design. He became a full academician in 1913. At the same time, Bellows’s deep interest in theories of color and composition, under the influence of which his art continuously evolved, indicated his fundamental affinity with more radical contemporary art movements. Indeed, Bellows was instrumental in the organization of the groundbreaking 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, commonly known as the Armory Show, which introduced American audiences to cubism, abstraction, and other modernist developments in art.

A prolific artist, Bellows was also a revered teacher, serving as a life class instructor (teaching the art of drawing from live models) at the progressive Art Students League in New York and a visiting instructor at the conservative school at the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1919. Widely respected, Bellows won several important awards for his work. His career was cut short when he died at the age of forty-two of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix.

Henri inspired Bellows to turn his attention to the portrayal of city life around him. Throughout his career, New York City and its inhabitants were an important fund of subjects. Bellows explored the variety of the city, from middle-class matrons in Central Park to poor urban youth at play and prizefighters locked in combat, and from the busy Hudson River to construction sites. In addition to such gritty urban themes, Bellows painted the sea and seafaring folk on the coast of Maine and idyllic rural life in Middletown, Rhode Island, and Woodstock, New York. He was also a prolific painter of portraits, both of sitters for commissioned likenesses and of family members. During World War One he began to produce dramatic images of the conflict and its heroes and victims. Bellows treated these themes not only in vigorously painted, strongly colored oils but in lithographic prints, which he began to produce in 1916. Since early in his career he had drawn illustrations for magazines ranging from conservative journals to The Masses, an organ of progressive politics.

Although never officially a member, Bellows exhibited with the group of radical realist artists known as The Eight; a critic derisively called them “the Ashcan school” because their paintings focused on the seamier side of urban life using a vigorous, anti-academic style. Bellows’s work shared these features, but it was also well-received by critics and fellow artists, even conservatives: for example, in 1909, he was the youngest associate member ever elected to New York’s prestigious National Academy of Design. He became a full academician in 1913. At the same time, Bellows’s deep interest in theories of color and composition, under the influence of which his art continuously evolved, indicated his fundamental affinity with more radical contemporary art movements. Indeed, Bellows was instrumental in the organization of the groundbreaking 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, commonly known as the Armory Show, which introduced American audiences to cubism, abstraction, and other modernist developments in art.

A prolific artist, Bellows was also a revered teacher, serving as a life class instructor (teaching the art of drawing from live models) at the progressive Art Students League in New York and a visiting instructor at the conservative school at the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1919. Widely respected, Bellows won several important awards for his work. His career was cut short when he died at the age of forty-two of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix.